Weekend rewind: Super Mario Part 2

In part 2 of our exclusive interview with Mario Andretti, the racing great tells Darren House about winning the Indianapolis 500, his toughest opponent, and surviving a triple backflip at 360km/h.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 2016

AUTO PARTS AND EQUIPMENT: YOU BROUGHT SOME UNIQUELY AMERICAN RACING TECHNIQUES TO F1.

MARIO ANDRETTI: In road racing you set up a car by having everything square, but in oval racing, because you only turn one way, you apply cross weight and stagger on the car. That was something I did in Formula 1. Every circuit has a couple of corners that you can throw away, and some key corners where, if you get it right, you can really gain a lot of time, that is what I would set up for. I would work with my rear stagger and cross weights, but the cross-weight was not something that you could determine by putting the car on the scales and saying, ‘Okay, we are going to do 30lbs across the back’. I had to do it by feel, so during practise I would come in and I would ask Colin (Chapman) to do what I wanted, and he would put it on the scales and say, “Oh it’s all wrong” and I would say, “No, no, no, don’t touch it!” (laughs). And it worked for me. I think I had an advantage in that respect.

FORMULA 1 IS A ‘DOG-EAT-DOG’ TYPE OF SPORT. WHAT DO YOU THINK OF THE CATEGORY GENERALLY?

I love Formula 1. It’s highly emotional, it’s big stakes and psychologically it becomes dog-eat-dog, you don’t give anything away. You want to be very selfish about things and unfortunately that’s the way it is when things are highly competitive. I think some of the drivers’ culture, perhaps not being available to their fans to some degree, is probably a bit wrong but some of it is also misconception. I never had any problem, personally. I felt, I do my thing, they do theirs, and I found, even today, I have a lot of friends in the sport. It’s like another family to me.

AS A RESULT OF THAT COMPETITIVENESS, THERE ARE A LOT OF INCIDENTS IN F1. THE CHAMPIONSHIP TRAVELS TENS OF THOUSANDS OF MILES AROUND THE WORLD, YET A CAR CAN BE ELIMINATED AT THE FIRST TURN, OR EVEN BEFORE IT.

The reason is everybody’s going for it because many times that’s the move of the day, but at the same time it can ruin your day so early, so it’s a double-edged sword. Even as a fan, when you’re watching, and of course the team as well, there’s nothing worse than being eliminated in turn one on the first lap. Unfortunately, I look back at my career and there are some moments I wish I could take back (laughs).

WHAT WAS YOUR APPROACH TO LEARNING A NEW TRACK ON RACE WEEKEND?

At any track you go to, you just have to deal with whatever is there, and it’s equal for everyone. Each driver has their own way of going about it. Many walk the tracks; I don’t think I ever walked a track in my life, but I like to go around with a regular car and be by myself. I never liked it when I was trying to learn a track, get it in my head, and someone would say, ‘Oh, I’ll come with you’ and I would say, ‘No, no, no, I’m doing it myself’, that way I’m not distracted. That was all I ever needed, quite honestly. Then you take the race car and that’s it, end of story. By the third run [of the weekend] you have a pretty good idea where things are.

TO BE SUCCESSFUL AT THE ELITE LEVEL, YOU HAVE TO BE VERY SELFISH. HOW DID THAT AFFECT FAMILY LIFE?

You had to have a lot of support around you and I have been very fortunate with my wife (Dee Ann), she was as solid as a rock. She was very unselfish and she knew this was the only way that I could be happy. I was the selfish one; I was satisfying myself with my career. We sacrificed vacations – all the travels we’ve done around the world have been in conjunction with races, and I never heard any nagging from her. Stability of family life was very important to me.

DID YOUR CAREER COST YOU TIME WITH YOUR KIDS?

Yes. I spent as much time (with them) as I could. I had them travelling with me all over the world at different times and so we did the best we could to keep it all together, and we did. When Michael was just a young lad, about six or seven years of age, the school teacher asked him, “What does your dad do for a living?”, and he said, “He goes to the airport and makes bread”. The reason he said that was because he used to ask me, “Hey Dad, what are you doing, where are you going?” I replied, “I’m going to the airport, I got to go make the bread (laughs)”.

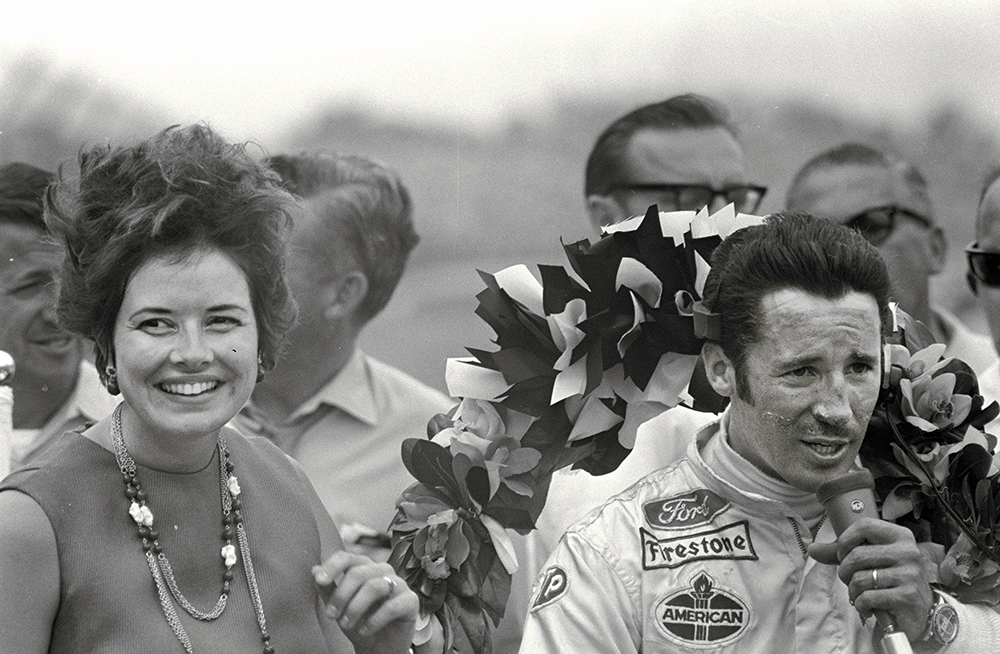

YOU WON THE INDY 500 IN 1969.

That was a very unlikely race (for me to win) because the car that I was driving was not the car that we intended to race. Our main effort was with a four-wheel-drive Lotus, a very technically-advanced car with some good aerodynamic pieces on it, but it was under-designed and we started having some suspension failures. I was setting some records in practise and the right rear wheel just sheared off and I crashed heavily. There was a fire and it destroyed the car.

The team ran three cars – two with Colin Chapman and one with me and STP – and they decided to withdraw all three cars. I was left with the car that we had started the season with (but at least) I had just come away from a win in California with that car. We only had one day to practice and I put it on the front row. In the race I was competitive and although I had overheating problems, the thing stayed together and I went on to win it.

It was strange, because the years before, especially in 1966, ’67, I had so much of an advantage with the car. I was on pole but then I had mechanical issues. Had I finished those races, those could have been two of my easiest wins anywhere. But ’69 was such an unlikely situation because I had so many problems in practice, yet we won the race. You just don’t know.

There were times later on, like in 1987, where I dominated that whole month. I was quickest every day of practice that I was on the track. I was quickest in qualifying and I led almost every lap in the race, but with 23 laps to go a valve spring broke, so go figure.

DO YOU GO INTO A RACE LIKE THAT THINKING VICTORY IS ALMOST CERTAIN, OR DO YOU HAVE NAGGING DOUBTS ABOUT RELIABILITY?

The reliability factor was always in the back of your mind, especially in those days. Nowadays, the engines are only run at about 95 per cent of their potential because of the rules. Formula 1 is the same way because they are limited in the revs. In those days we extracted every ounce out of the engines, so it was different. Going into this particular race, my engineer was Adrian Newey, who of course now is with Red Bull in Formula 1, and even then I considered him to be the best ever. I felt so, so confident that I figured, ‘Today, they have to beat me’, I knew I had them all covered, and I did. I had a one-lap lead with 23 laps to go.

The engine mechanics are always screaming at you, “Keep the revs down, keep the revs down”, so I thought, ‘Okay, now I have a big lead, I am keeping the revs down’, and that’s what did me in (laughs). The engine designer, Mario Illien (Ilmor Engineering), said that I was running a rev range with bad harmonics – in other words, if I had run 600 revs more, the chances are I would have gone to the end and won the damn thing.

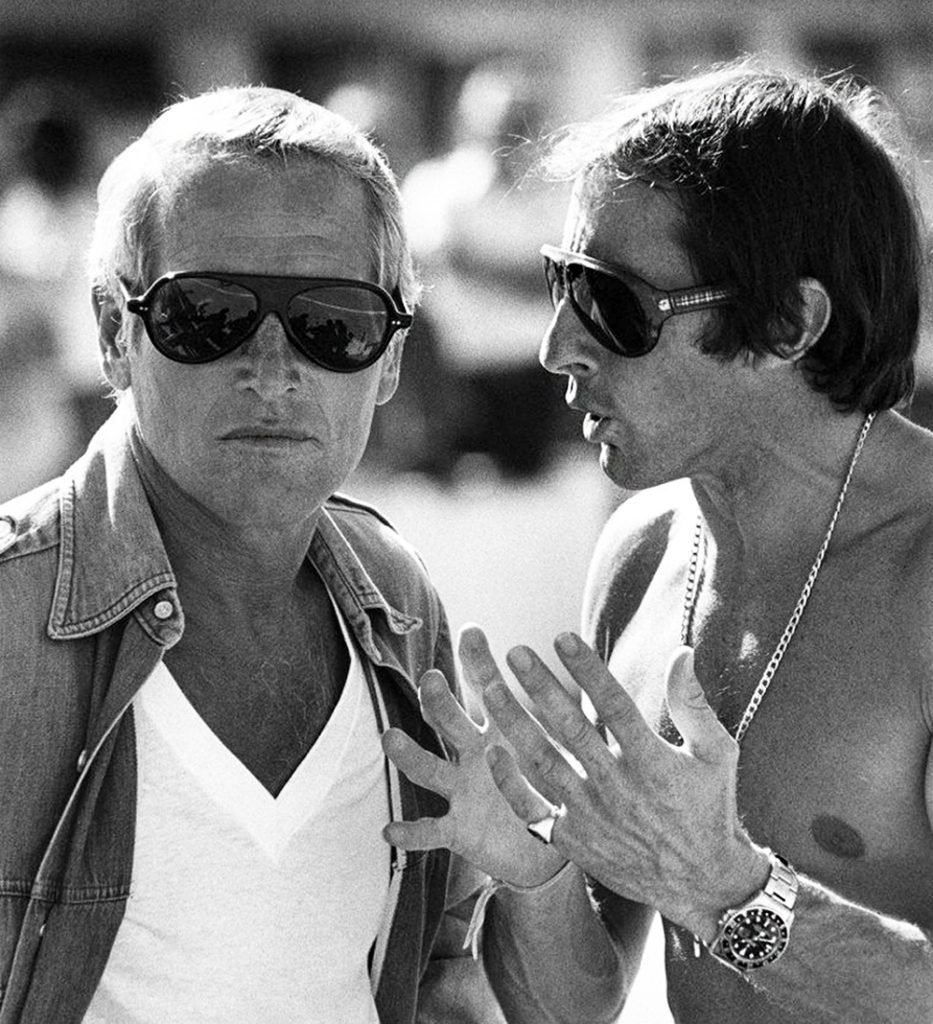

I have nothing but really good things to say about Paul Newman. Every memory is a good one. He was a good, good man.

WHO IS THE TOUGHEST DRIVER YOU HAVE RACED AGAINST?

Each decade there were one or two drivers who were a big thorn in my side – it was never just one individual – and it’s the usual suspects, the ones who did all the winning. When I broke into Indy Cars, AJ Foyt was the yardstick and when I broke into Formula 1, there was Jackie Stewart, but along the way there was always somebody else. The biggest satisfaction that I derived came in the first two Formula 1 races that I won – Jackie Stewart finished second, and I thought it couldn’t be any better than that because I considered him to be the best at the time. It was the same thing with Foyt. That is how you measure yourself. But as you go on, there are many others that come along. At that top level, there is a lot of talent that you have to deal with.

YOU DROVE FOR PAUL NEWMAN. WHAT WAS HE LIKE?

Paul Newman was an incredible human being, from every stand point. As the team owner, he was so incredibly supportive and passionate about the sport. A lot of people would think he had just a superficial involvement (but) it was nothing like that. It was the opposite. I take some credit for bringing him into the sport at that level, and I spent the last 12 years of my career driving for him, so we developed a friendship that was so precious to me. I have nothing but really good things to say about him. Every memory is a good one. He was a good, good man.

HOW DID YOU BRING HIM INTO INDY CAR?

He was an owner in the CanAm series and he had wanted me to drive for him, even when I was driving Formula 1, but I could never find the time. By the early ’80s, CanAm had pretty much gone by the wayside (so) when I came out of Formula 1, I thought he could be a great team owner in Indy Cars. I had also developed a friendship with Carl Haas, who was the Lola importer in the United States. He was also in the CanAm series and I figured maybe I could marry those two guys because that would make a formidable team, and I was able to accomplish that. That was great for me because from that point on, until the end of my career, I won 18 Indy Car races for them.

We touched wheels a bit and I was somewhat upset, and then all of a sudden I said, “Oh gosh, that’s my boy”.

YOU RACED AGAINST FAMILY MEMBERS.

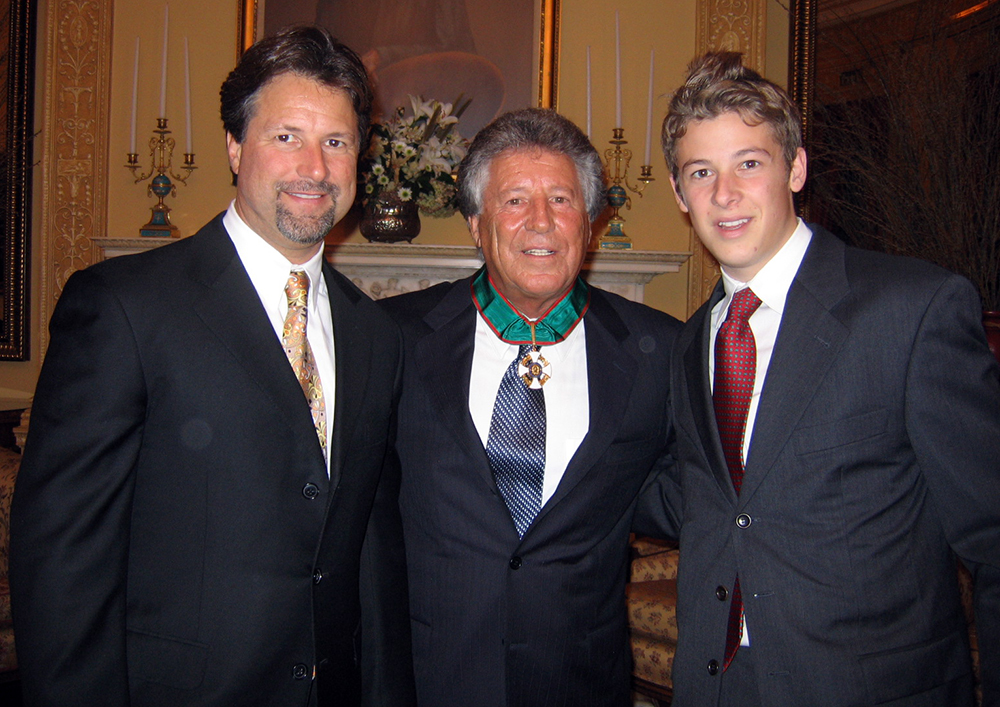

That was one of the best moments of my career because I raced against both of my sons, Michael and Jeff, and my nephew, John. I also had Michael with me in the Newman Haas team, and we had so many podiums together. We started on the front row 10 or 12 times, which was an incredible experience. One year in Milwaukee, it was an all Andretti podium – Michael won, John came second and I finished third.

I’M GUESSING THERE WERE NO FAMILY FAVOURS.

I remember very clearly the very first time that Michael made a competitive pass on me. We were at the Grand Prix in New York, at the Meadowlands. It was a street race, he was in great form and he really forced the pass through a hairpin. We touched wheels a bit and I was somewhat upset, and then all of a sudden I said, “Oh gosh, that’s my boy” (laughs). It was sort of a double-edged sword but I was happy for him. Then, in 1986 in Portland, Oregon, we had the closest finish ever – 0.007sec and I won, but Michael should have won. He had fuel pick-up problems on the last lap and I nudged him at the finish by about three inches (laughs). He was pissed off about it but he came around after a while because it was Father’s Day and he said, “Oh well, happy Father’s Day”. The thing that was good about us being teammates was that we were totally honest with one another, not all my teammates were like that. That was great. It was good for my career towards the end, because I felt I was measuring myself against the best. Michael was a really good driver. As good as I have ever raced against.

LIKE YOU, MICHAEL RACED IN FORMULA 1, BUT ONLY FOR ONE SEASON.

He probably went to the best team at the worst possible time, mainly because of Senna – Senna was actually very helpful, very good to Michael – but they lost their big advantage, they lost their Honda engines and so they were not able to do any testing with the actual car until they went to South Africa for the first race. That was the first time Michael even saw one. He did some testing at Silverstone with a car that was a year old, so it was not realistic to some degree.

On top of that, they introduced a 23-lap rule where, during the free practice period, the maximum laps you could do was 23, which was stupid, and it really hurt someone who was brand new to the car and brand new to the track.

The one good thing was that as the season progressed, Michael did really well. He came away with a podium on the last race that he was allowed to run. I think Michael could have probably fought a little harder for the seat for the following year, but Ron Dennis told him he could not guarantee he would pick up the option until November. Michael said, “Well, what if you don’t? I don’t have a drive for next year. I can’t do that”, so he opted to make a deal back in the ’States. It was unfortunate.

I think quite honestly Michael’s style was perfect for Formula 1 – flat out from the beginning and I think he would have done really well. Michael was a very, very good driver. As good as I’ve ever come up against, and not because he’s my son, it’s because he proved it over and over. I wish he really had have had a fair chance in Formula 1 but I don’t [just] blame everyone else, I blame him as well because he probably could have said, ‘Well, you know what, I’m going to stick to Formula 1 for a few years until I achieve my goals’, but he didn’t do that.

MARCO ANDRETTI, MICHAEL’S SON, YOUR GRANDSON, HAD A RUN WITH THE HONDA FORMULA 1 TEAM.

I would have loved to have seen Marco pursue that a couple of years ago. He did two tests for Honda, but it was so political. It upset me quite a bit because he was really doing well. In his first time in the car, he was on the pace with [Rubens] Barrichello and Jenson Button but they never really gave him the opportunity to lay down the ultimate lap. I asked for new tyres and they filled him up with fuel to do a race run. Give me a break, the young lad just wanted to know what he could do under qualifying conditions, and they never gave him that opportunity. That part was very political. I was quite upset about it.

GIVEN THAT, WHAT WAS THE PURPOSE OF THE SESSIONS?

Primarily because his father had the factory Honda team in Indy Car and they won a championship so Michael asked Honda to give Marco a go but there were certain conditions. They didn’t like the fact that I went along. I said I’m doing it, but they pretty much kept me at bay. It was weird, actually, at that point. Certain people there, team members that I will not name, I didn’t like them at all. They were disrespectful.

WAS IT HARD TO COME TO THE REALISATION THAT YOU NEEDED TO STOP RACING?

That was really tough. I love driving so much and I didn’t want to stop but I knew that it had to come to an end and the decision had to be made. My biggest fear was to overstay – I have seen some of my colleagues stay too long and becoming uncompetitive. I figure when you retire, that is what you are remembered for and I didn’t want to do that. I was fortunate enough to have stretched my career until the age of 54 but I felt I was competitive. I didn’t win a race in my last year but I won a race the year before, and I still felt that I had something in me, but I didn’t want to test it to that point.

WERE YOUR LAST FEW LAPS AT LAGUNA SECA EMOTIONAL, OR DID YOU ONLY THINK OF IT AFTER YOU STOPPED?

It was a very emotional weekend for me because I didn’t want to be thinking, ‘Okay, this is my last race’, so I just tried to stay in denial because I didn’t want to be that depressed. But the decision was made. Even my wife said, “Why didn’t we discuss it?” and I probably should have, but I didn’t. I just wanted to make that decision myself, and then I had second thoughts – I really did. When I stepped out of the cockpit, I felt that maybe I shouldn’t have (retired) but as more time went on, the happier I was with the decision because the memories of my career are totally positive. The good thing was I raced another three times at Le Mans, and now I drive the two-seater car (promotional Indy Car), which is fun. It goes pretty good, pretty fast.

I go to six or seven Indy Car races and drive on Thursday, Friday and Saturday and on race day I’m the first one to go flat out, with a Honda contest winner who rides with me as a passenger, at the start of the race. Just before the starter gives the ‘green’ to the field, I do the first hot lap and when I join the back of the field the starter gives the green, so it’s exciting for someone who has never had that experience, especially at Indy where you’ve got 300,000 people. It’s fun.

HOW IS LIFE IN RETIREMENT OTHERWISE?

My son Michael continued to race, and my nephew John, so there was good reason to stay with the sport, but I think the part that helped me most was I very fortunate to maintain relationships with companies I worked with. My relationship with Firestone for instance, is very much racing related so it keeps me involved in the sport and gives me reason to stay close to it. That allowed me time to condition myself to the fact that I don’t have to be so disciplined on the night before the race. Many times, when I was racing, the night before you had to leave a party at 8 o’clock when everybody was beginning to have fun, and I thought someday I won’t have to do that. When it came to that point, I wished I didn’t have to stay at the parties (laughs), so there was a lot of re-adjustment. I drove for so many years and I became so used to things – life took shape and then it changed so dramatically. It took me a while to get used to it.

I did three flips backwards. According to the telemetry, I was doing 222mph (357 km/h), so I started flying like an F16. It didn’t look very good from where I was watching it, but I got real lucky – we landed on the wheels and I only had a few bumps here and there.

WHAT DID YOU THINK WHEN ASSOCIATED PRESS NAMED YOU DRIVER OF THE CENTURY?

When people recognise you in that fashion, really you don’t expect it but it’s the ultimate compliment anybody could pay. There’s no better reward for your career, for your work, than to be recognised in a positive way for it.

IN 2003, AT AGE 63, YOU RETURNED TO THE INDIANAPOLIS MOTOR SPEEDWAY AND CAME CLOSE TO LOSING YOUR LIFE.

One of Michael’s drivers, Tony Kaanan, suffered a hairline fracture of the wrist in the race before Indy practice was about to start and so there was a question as to whether he could qualify the car – there was no question that he could race it because he had three weeks recovery time, and so my son, Michael, was wrestling with the idea of who he would get to qualify the car. My daughter (Barbra) said casually to Michael, “Why don’t you have Dad do it?” Michael then looked over to me and said, “Dad, what do you think,” and I said, “Well, if we do a proper test and evaluation, certainly I’ll do it.”

There was an open test and I felt right in my zone immediately. After just two runs I was right up to speed and everything felt normal – I have done so many miles at Indy. We learned a lot and at the end of the day, when I slip streamed, I was quickest at somewhere around the 225 to 227mph (362-365 km/h) range, and so I wanted to go out and put a big lap on the board by getting a good tow. On the last run of the day I went behind Kenny Brack, and going into turn one he exploded the engine and crashed very heavily. I was only a second or two behind him and when I arrived on the scene, there was [debris] all over the place. A chunk of the safe wall, the energy absorbing walls that had just been installed, was right in the middle of the racetrack and I thought, ‘Okay, I’ll hit it, it will be no big thing’ because it is like Styrofoam (but) when I hit it, it just launched the car – I did three flips backwards. According to the telemetry, I was doing 222mph (357 km/h), so I started flying like an F16. It didn’t look very good from where I was watching it, but I got real lucky – we landed on the wheels and I only had a few bumps here and there.

DID YOU HAVE TIME TO THINK ABOUT WHAT WAS HAPPENING DURING THOSE BACKFLIPS?

The only thing you are thinking is, ‘I wonder if it is really going to hurt when you finally hit something’ (laughs), because I knew it was going to land somewhere – I just didn’t know where. But it happens in a nanosecond – everything happens so quickly, but I thought I could really be hurt on this one.

WHAT WERE YOUR IMMEDIATE THOUGHTS WHEN THE CAR CAME TO A REST AND YOU WERE OKAY?

You thank the man upstairs. I am religious enough to do that. Something like that is strictly luck, it could have gone a different way, it could have slammed me against the wall – so many things could have happened differently, but they didn’t, so it’s one of those things where you think you have dodged another bullet. I dodged quite a few of them in my life. I take nothing for granted. I know how fortunate I have been. I figured maybe this is the one, but it wasn’t.

SINCE THE DEATH OF DAN WELDON IN 2011, THERE’S BEEN A LOT OF TALK ABOUT NEW SAFETY DEVICES, SUCH AS ENCLOSED COCKPITS. WHAT’S YOUR VIEW? [INDYCAR IMPLEMENTED THE AEROSCREEN IN 2020].

From a safety standpoint we’re enjoying the best period ever. You look at some of the accidents and [straight afterwards] the driver is ready to jump into another car, it’s amazing. Poor Dan Weldon, his [situation] was just like the perfect storm, it was one of those freakish situations that happens. Unfortunately, the sport is not 100 per cent safe and never will be, just like you are never 100 per cent safe on the road, let’s face it. So, no matter what measures you take – like cockpit protection – there is always going to be something there, but those situations are few and far between. Like I said, Dan Weldon’s situation was just one of those unfortunate but freakish things. There were other cars that were upside down, up in the air and so forth and no body had any injuries.

THERE ARE PLENTY OF NICE PLACES TO LIVE IN THE USA, BUT YOU REMAINED IN NAZARETH.

I really love the area. It’s got everything we enjoy and as we travelled so much with my racing, it wouldn’t matter where I live, to some degree. I’ve had pressure to move to the west coast for whatever reason; sometimes teams were based there but I always resisted that because where I am, the accessibility to Europe is very good. I’m also close to New York and the major cities, so for the amount of travel that I used to do abroad, I thought this was the best option. I also raised a family here, I have a considerable amount of property that I own just north of here, in a little bit of a resort area, and we have everything we want. It’s a playground for us and I could not duplicate that anywhere because I own a couple of lakes; 600-plus acres and we have a good time there.