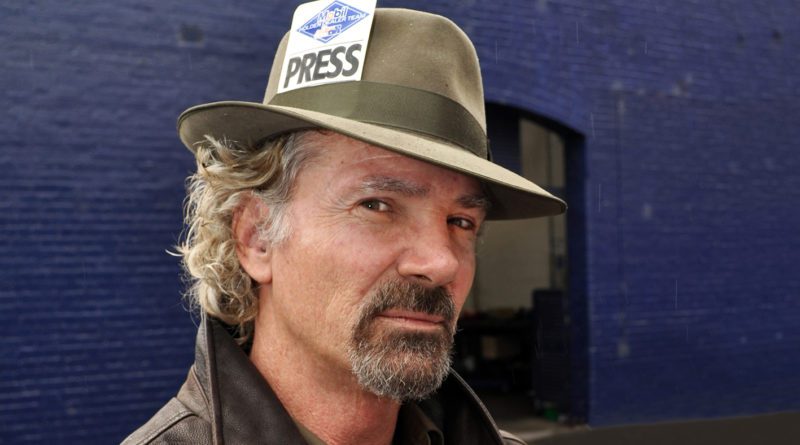

The write stuff – Mark Fogarty

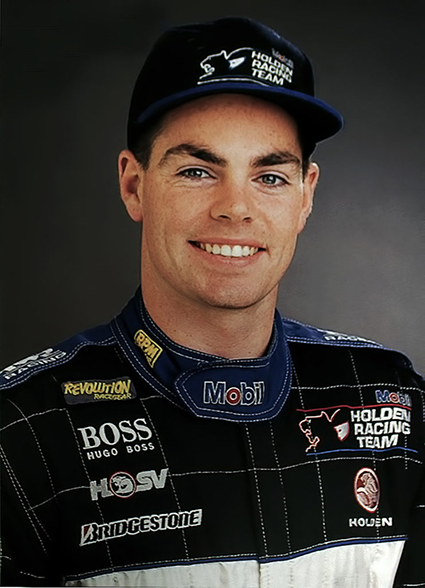

Australian journalist Mark Fogarty is motorsport’s go-to man when the tough questions need to be asked and the big events covered. Moving to the other side of the voice recorder, ‘Foges’ told Darren House about his 48-year career.

Interview: Darren House Photos: Darren House; autopics.com.au

Mark, you’re one of motorsport’s most feared reporters. How did it all begin?

I have been a car enthusiast for as long as I can remember. I have been told that when I was three years old I could name every car on the road.

When I became a teenager I was even more obsessed with cars and car racing and would read all the magazines I could get my hands on. I educated myself in the whole motoring and motor racing worlds and their histories by going into second-hand book shops and buying old magazines.

At some stage I deduced that being in the press was a way of getting into car racing for free, (so) I called James Laing-Peach, who at the time was editor of Auto Action. I asked, “If I was to write a story for Auto Action, would you look at it?” He said, “Of course we would look at it”, (but) he was probably just dismissing this annoying kid. I, of course, took it to be a firm commission.

What do you remember about that first story?

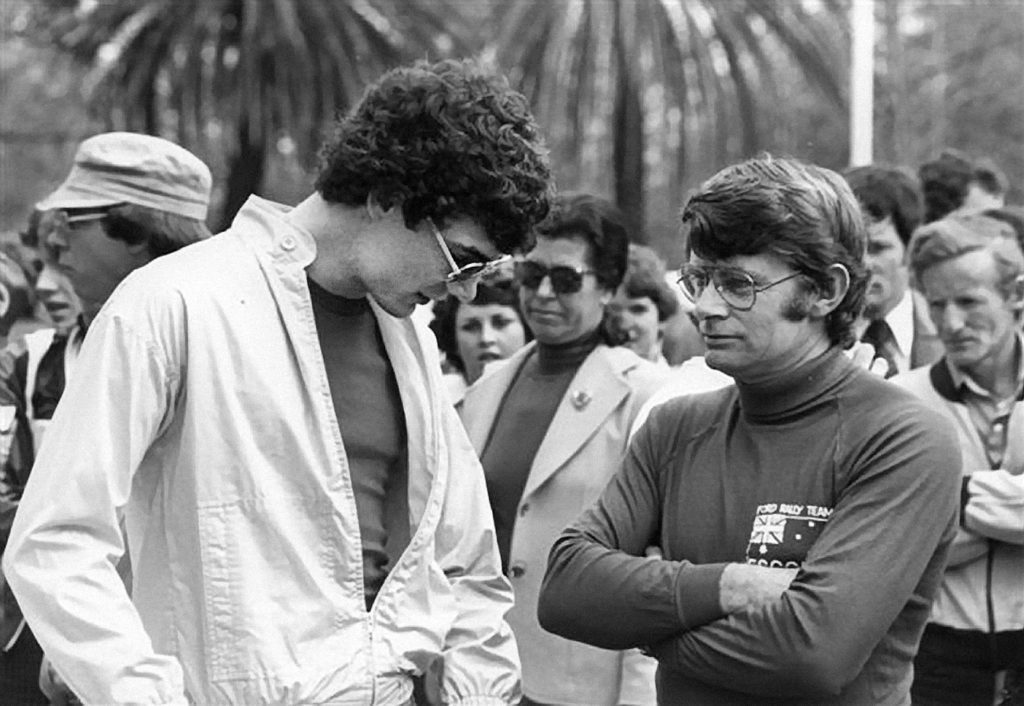

I went to Sandown Raceway in February of 1972 for the Tasman Cup round and I bowled up to Graham McRae, who was one of the gun drivers. He had just begun to race a car of his own construction and as a kid I was curious how this had come about.

So I bailed him up, introduced myself and we talked for probably 20 minutes. I went away, wrote a story – it was handwritten – and bowled into the Auto Action offices, submitted it and lo and behold, it was published.

It was a terrible story – how I ever parlayed that into a profession is beyond me but I was certainly persistent and relentless. From there I did more stories for Auto Action and broadened into writing for hot rod magazines, motorcycle magazines and drag racing magazines. That was when I was 15.

I still look back at my early stuff and I shake my head. I wonder how I got as far as I did. I really think that as a writer I didn’t hit my straps until the early to mid-’90s. I always had the basics but refining the craft probably took 10 to 15 years and that is probably not unusual.

Peter Brock often told people that you once arrived for an interview riding a (push/kick) scooter. True or false?

It has become legend so it may as well be true. It was started by Peter Brock and then perpetuated by (Ford team boss) Howard Marsden who also used to joke that I turned up to interview him on a scooter. It is not true in either case but I did turn up to interview them in my school uniform and with my school bag.

In Brock’s case I got the tram down from Malvern, where I went to school at De La Salle College, to Glenferrie Road and then walked up Burwood Road to the old Holden Dealer Team headquarters, which is a grandiose term for an old backstreet garage. We were outside, I stood and he leant against his company car, which in my memory was an orange four-door Monaro and I had a clunky, old fashioned cassette tape recorder with a microphone on a long lead.

So, I am sorry to say it is a myth, but it symbolises the bizarre nature of a school kid turning up for an interview wearing his school uniform – not quite short pants, I don’t believe. I would have been in my college’s Winter uniform, which was a grey suit.

As a 15 year old, did you have any trepidation about interviewing big name drivers?

Oh no. I was fearless. Absolutely fearless and irrepressible. I was never intimidated. As far as I can recall, it never occurred to me. For a kid and for someone with no established track record, the amount of confidence I had and how bold I was in fronting people and getting interviews was remarkable. It certainly helps to have more front than Myer when you are starting out.

Just the same, not too many sports stars would give a school boy a hard time.

No. When I was starting out I think most people were bemused that there was this kid running around. I trod on a lot of toes and a lot of people didn’t like my style and thought I was far too big for my boots, and I am sure they were quite right at the time but I have never stopped to think about that. It has never slowed me down.

How did you become a professional writer?

In my final year of high school I managed to make connection with the late Mike Cable, who was sort of the doyen of motoring journalists back in the day. Mike was the long-time motoring editor of The Australian newspaper and he always encouraged young journalists, and young drivers. I managed to convince The Australian to take freelance contributions on motor racing. Quite a few of my stories were published and that resulted in a cadetship on The Australian sports desk, ostensibly as a football writer.

That was ironic, if not laughable because I managed to grow up in Melbourne being totally disinterested in Aussie rules football yet my first job primarily was as a trainee footy writer. I stumbled and bullshitted my way through that but it was a means to an end because as well as writing footy news, they learned after the first time they sent me to do a game that match reporting wasn’t my strength.

So they gave me a desk job chasing news, which I have always had an ability to do. News is what I like chasing. As well as my footy stuff, it gave me the opportunity to write motor sport stories and they were getting published with unusual frequency.

Journalists quickly realise that sports stars aren’t necessarily as nice as their public images portray them to be. As a young person, how did you cope with that?

I have a reputation for being nosey and I was a very confident young bloke, so I would just bowl up to sports people completely fearless. I suspect there was a bit of resentment that I was being a bit too brash and bold for a young bloke but I was getting published all over the place and making a name for myself quite quickly, so it obviously worked.

There were some people who weren’t too happy dealing with me in the early stages but over the years some of those people and I ended up having a very good rapport, because despite the hazards of my approach, it seems to have established some sort of respect. People don’t have to like you but they will work with you if they respect what you are doing.

I have upset a lot of people over the years but few refuse to speak to me now.

Over many years I have found that the direct approach works. People might be uncomfortable with the questions but they seem to understand there is no agenda.

Few people refuse to speak to you now. Who refused at the time?

I am sure Alan Jones has told me to f*** off, and Allan Grice. Dick Johnson has come close. It clearly had no effect on me because it hasn’t been etched in my memory. I have had more than a few choice words from Russell Ingall, despite the fact that I have rarely spoken to him in the last few years. But the times I have, it has almost routinely involved colourful language in my direction.

You don’t always see it coming.

It can be unpredictable. Sometimes when you are expecting a blast or an uncomfortable conversation they have not been worried about it and just shrugged it off, or they just haven’t heard about it yet.

On the other hand, it is quite amazing that inconsequential things can actually get a far bigger reaction and cause more drama than something that is blatantly inflammatory. You can never be sure if you are going to encounter a person’s wrath, just as you can never be sure they are going to be in a good mood or happy to talk to you.

I was very lucky, all these things increased my notoriety and my reputation as the man to be feared in an interview situation, real or perceived, and it just helped my career. Once a reputation is earned it is very hard to lose.

Although I maintain that reputation today, I don’t ask questions so aggressively. I don’t need to and also, with maturity comes different ways of asking the same question. I think there has to be a bit of professional decorum. Fans on the other hand are quite savage. If they want to know something they just go for the jugular.

What’s the most important part of your job?

As a journalist, your primary function is to break news – to find out what is happening, either before it happens or to find out things you are not supposed to find out. That’s what drives me. Just going to a press conference and reporting what was said, in that controlled atmosphere, is of no interest to me whatsoever.

Digging around, talking to (news) sources, piecing together various facts and coming up with a breaking news story, that’s what gets me excited.

For example, you learn ‘driver A’ is going to leave ‘team A’ and join ‘team B’ next year, and if he is a superstar, that’s a great story.

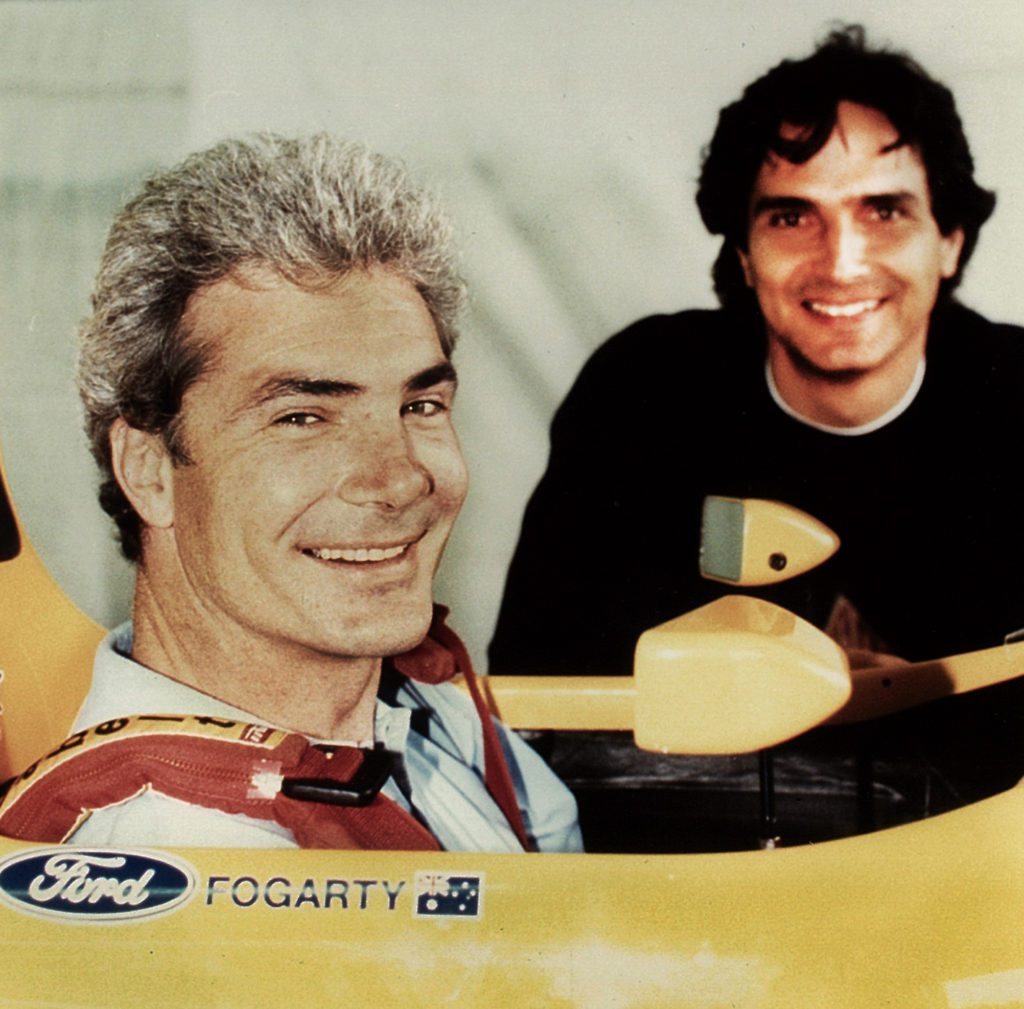

One of your more famous scoops upset Allan Moffat.

Moffat was most upset, understandably, because he had got this new great big sponsor for the Mazda RX-7 and he was trying to keep it a secret for the big reveal. I blew it entirely. Like most stories, I probably stumbled upon the fact that Peter Stuyvesant was going to back him.

You are also known for your probing question and answer interviews. How do you prepare for them?

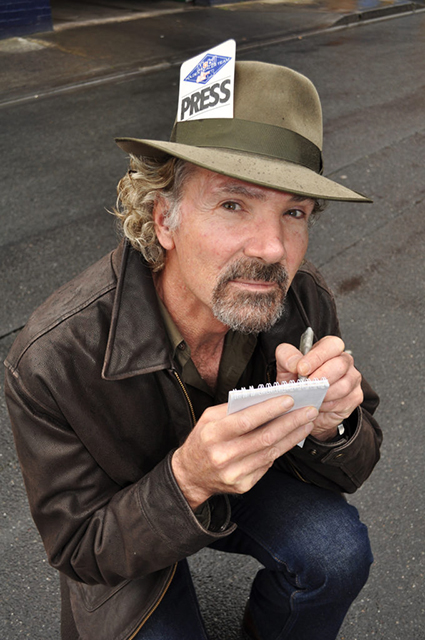

I rarely write down the questions, and haven’t done for probably 35-odd years. It would only have been in the very early stages that I wrote down questions. The most I do now is jot down a couple of key points and subjects I want to tackle.

Most of my interviews are pretty much off the top of my head and that comes with knowledge that comes from experience. I don’t have to research these people; I am acquainted with their careers and their personalities and what they are doing. In an interview, I think that helps the flow of the conversation because I am not always referring to notes.

A lot of interviewers lose the plot simply because they are not listening to the answer; they are too busy concentrating on asking the next question. If you don’t listen, you are never going to get a good interview because it has to be an exchange, rather than just question, answer, question, answer.

One of the greatest practitioners of the art of the interview was Michael Parkinson, and one of the reasons he was successful was that he listened to people, would pick up on what they said and extend it. Other interviewers stick rigidly to their questions when there is stuff in the reply that begs to be pursued.

You use the word ‘art’.

I think interviewing is an art and I like to think in motorsport journalism terms, particularly in Australia, that I re-invented the (Q&A) interview because a lot of other journalists dismiss the format. They say, “Oh, it’s lazy journalism”. Well, it is if it’s done badly but if it is properly done, there is nothing more transparent.

You are interviewing someone in depth and you are taking a lot of their time and you are putting down their thoughts. If you reprint it as your question and their answer in its entirety – there is always some editing going on, but essentially in its entirety – I can’t think of anything that is more transparent. It’s what you asked and what they said, without any interpretation or editorialising. The reader can then make their own judgment about what was said.

You have actively built the ‘Foges’ brand. You also once described flamboyant former racer John Goss as a “Shameless self-promoter”. Would Goss reply, “Right back at ya, Foges”?

He might have some cause to, but as a general rule I wouldn’t describe myself as a shameless self-promoter. It is the nature of the business; you have to promote yourself subconsciously. As a journalist, your name is your brand and I have a long established brand on that basis, but I don’t go out of my way to promote myself. I don’t stick my head in front of the TV cameras as some other well-known journalists do.

I am tall, I have had grey hair from an early age and I have a distinctive voice so I stand out. That’s not a bad thing because it is a competitive world, and if you don’t stand out from the crowd it’s more difficult to get things done.

Who are the most challenging drivers to interview?

Two examples of drivers who were hard work, but have improved, are Glenn Seton and Craig Lowndes – neither had anything to say. There was no depth to what they were talking about, particularly Craig Lowndes, and there was a time when I used to find interviewing them frustrating. Glenn now is quite interesting; quite chatty. And he now has something to say about a number of subjects; the same with Craig.

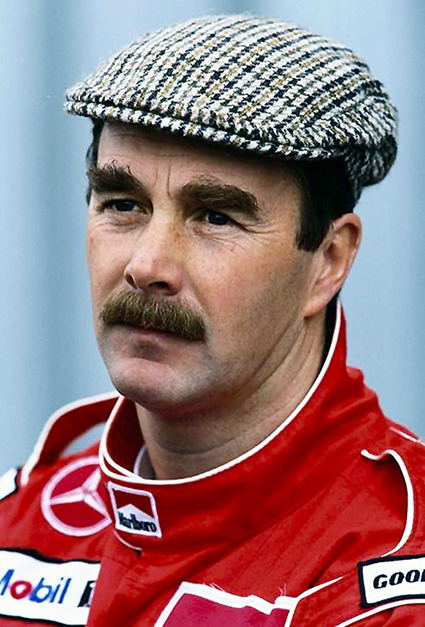

Nigel Mansell was funny, simply because he had a very poor command of the English language and would get words wrong and phrases the wrong way around. He couldn’t plumb the depths, whereas Ayrton Senna had the ability to describe very vividly the sounds and sensations of driving a Formula 1 car much better than anyone I have ever come across, which is very difficult.

What do you put that down to?

Most athletes can’t describe what they do in any depth because it comes naturally to them; they find it very difficult to intellectualise their talent. Senna was an exception in that he could, and once you got him going he would speak very eloquently and passionately. He would take your question and think about it and give you a very long and considered answer.

It was quite unnerving sometimes because I would ask a question and there would be a long pause that seemed to last a lifetime. It could be up to 20 seconds and when you are sitting there, holding a recorder, waiting for an answer, it seems like an eternity. But that was simply because he was taking the trouble to take the question on board and to think about a considered answer.

How did your international career begin?

Through radio in the early to mid-’80s I was covering international tennis and other big events, such as the golf majors and the Americas Cup yachting for radio networks in Australia, NZ, the UK and the US. That led to me moving to the UK in ‘87. I started covering some Formula1 races in amongst all of that and eventually I stopped doing radio in ’91.

I then went full time into Formula 1, so I was ‘Johnny On The Spot’ during the whole Aryton Senna/Alain Prost /Nigel Mansell era.

Were you as brash on the international stage?

In press conferences I employed a deliberate tactic. I was loud, I incited comment by asking very direct questions and just by that very fact I stood out from the crowd among the media. Some drivers dealt with it well, particularly Senna who seemed to relish the challenge of difficult, thought provoking questions. Others, not so much.

Nigel Mansell didn’t like me at all. We had some pretty interesting runs ins to the point where at Barcelona in ‘92 he accused me of being on drugs. He took a question I asked about the extent of his domination in the ‘all singing, all dancing’ Williams, which had active suspension and all of the other electronic gizmos, to be a criticism of him – that it was the car doing the winning and not Mansell. And of course, with Mansell, it was all about him. That caused a big stink.

We made up a later at the Monaco Grand Prix. He came up and apologised but he leant so far into my ear I thought he was going to kiss me.

Despite your brashness and reputation in Australia, were you ever intimidated when grilling F1 superstars?

No, because I had done a lot of work overseas already in different sports so there wasn’t anything intimidating about going into Formula 1. I was dealing with the likes of John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors, Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Jack Nicklaus, Greg Norman, John Bertrand – the Americas Cup winning skipper and the US skipper, Dennis Connor – so I had some background in dealing with major sporting personalities. It never crossed my mind that it was something I couldn’t do.

How did you find Michael Schumacher?

Michael never really had much to say, he never really wanted to say much, so I found it frustrating interviewing him. He was just so careful not to let people know what he actually thought and almost remained behind a mask. Senna showed his passion and people loved him or loathed him, but they had a very clear opinion of him. Michael just didn’t inject that emotion. It’s a bit like comparing Peter Brock’s popularity to that of Mark Skaife.

Skaife has a tremendous record of success and he is much admired and respected, but there is something there that tells me he is not as loved, and his memory will not be as cherished like the memory of Peter Brock.

You feature in the Ayrton Senna documentary, not for asking him a trademark hard question but a rather innocuous one.

It was a very innocuous question, so innocuous I have no idea why I asked it. I think it was because the Adelaide GP in ’93 was his last race for McLaren as he was moving to Williams and for some reason it occurred to me to ask him a question that really hadn’t been asked before, which was, “Who did he regard as his greatest rival?”

I was expecting him to name Prost yet he named Terry Fullerton, a guy he raced against in karting. I think there was one person in the room who knew who Fullerton was, Chris Lambden, who was an ex-karter, and he knew that Terry was one of the greatest ever kart racers. I suspect there was also a back-hander there by not mentioning Prost but it certainly was a surprising answer.

It has proved to be quite significant in setting the stage for the whole Senna documentary and that is why they have used it as a very poignant moment right at the end. I was very flattered that they included my question and gave me credit for it on the screen. A portion of that sound bite is also at the beginning of the movie and it sets the whole tone.

Do you wish you had asked that question in private rather than in a press conference full of other journalists?

Of course, and increasingly in recent years I am almost mute in press conferences, which surprises a lot of people because for many years it was almost my signature, But two things; as I said before when I first went into Formula 1 and other sports, it was a deliberate tactic to establish my name and face very quickly.

The other side of that is F1 drivers have always been difficult to get (one-on-one) access to, you can’t just sit down with them like you can a Supercar driver – although even that is changing – and ask them the questions that you want.

So while in principle I have never wanted to ask my good questions in a press conference because you are just feeding everyone else and giving them stories, sometimes you just have no choice.

These days I rarely ask questions in press conferences for the simple fact of why do other people’s work for them? And I am now in a privelleged position – if I want to ask someone something I can pretty much go to them directly and ask them.

You were at Imola when Senna and another driver, Roland Ratzenberger died.

It was a horrible weekend, but it’s a bit Dickens-like… “It was the best of times; it was the worst of times because I won a Porsche. There was a raffle at a media function run by Porsche and the prize was a 964 Club Sport. It was an amazing, surprising thing, but the rest of the weekend was just horrendous. Rubens Barricello had this huge shunt that almost killed him and certainly rattled Senna. Then Roland Ratzenberger died in a horrible accident during qualifying on the Saturday and that really rang Senna’s bell; that really un-nerved him. And then the next day Senna died in a freak accident, the cause of which we still don’t know. It was the worst weekend motorsport-wise that you could ever imagine, but then in amongst all of that, I experienced a stroke of great fortune.

Amid a sea of grief and shock, you then go to work, reporting the death of Senna and Ratzenberger. How difficult was that, given your relationship with them and the wider F1 community?

You just do it. It’s the job. I had to go back to London to write what was billed as the last print interview with Senna because I had spoken to him on the Thursday; the whole background to that and why the interview was never finished is a story in itself. I then ended up making appearances on breakfast television in London talking about it and I guess I was just so busy I didn’t think about it.

It wasn’t until later that it really struck me. Senna’s death affected me because we had, had a good professional rapport and I enjoyed talking to him and he apparently enjoyed talking to me. It wasn’t just another driver dying; it was someone that I had, had a lot to do with.

Unfortunately I barely knew Roland Ratzenberger but his death deserved a lot more recognition that it got. His death gets lost and that is a tragedy because Roland was no less a person.

You have also tried your hand at corporate public relations.

I have only had two corporate jobs. The first was a 15-month stint in the PR department of Holden in late 1979, early 1980 and I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was an interesting job, and very interesting people to work with. I spent some time initially in the NSW office, as assistant to the then NSW PR boss, Mark McGuinness, and then I got transferred to head office, mainly as a speech writer.

I ended up leaving for two reasons; Holden was in a very difficult position in 1980, they were heading for bankruptcy and they had to be bailed out by (General Motors) Detroit, so they weren’t spending any money on PR programmes. Consequently I was getting bored.

And I made the mistake of taking a holiday and going to the Americas Cup in 1980 at Newport Rhode Island and covering that event. That re-ignited the journalistic spark and my love of radio, so early 1981 I went back into that medium and parlayed that into international sports reporting.

The second time around was working for the Australian Grand Prix Copration as Corporate Communications Manager. It looked like the dream job to me and that is why I pursued it very aggressively, and I got the job in the middle of 1997.

I lasted eight weeks and got fired. I’m not quite sure why, it was never really spelt out and they didn’t have to because I was on probation. I obviously stood on some toes somewhere and got some very senior people offside, so off I went.

It was devastating at the time – I wasn’t used to that kind of failure and it was a job I thought I was very well equipped for. Had I been able to do the job as I thought I was supposed to do it, it probably would have worked out well.

You have returned home to where it all began – Auto Action, a magazine you continued to contribute to over the years.

Auto Action has never been far away. I started my writing career there and I have been backwards and forwards writing for them and other people but I have always come back. I stopped writing for them in the mid-to-late ‘90s and never really got back until then editor Allan Edwards invited me back in 2000, for which I was very grateful.

I have been writing continuously for them since then and I had a short stint as editor when they moved the magazine from Melbourne to Sydney and changed its format. It was a post I would have expected to achieve when I was in my 20s. A lot of people predicted I would become editor of Auto Action but I went elsewhere and never got that opportunity. I have been an editor of a number of publications but clearly I am not cut out to be an editor, which is essentially a managerial role. I am much better as a hired gun and left to run loose around the place and find stories.

WORDS: DARREN HOUSE PHOTOS: DARREN HOUSE; autopics.com.au