Weekend rewind: Super Mario Part 1

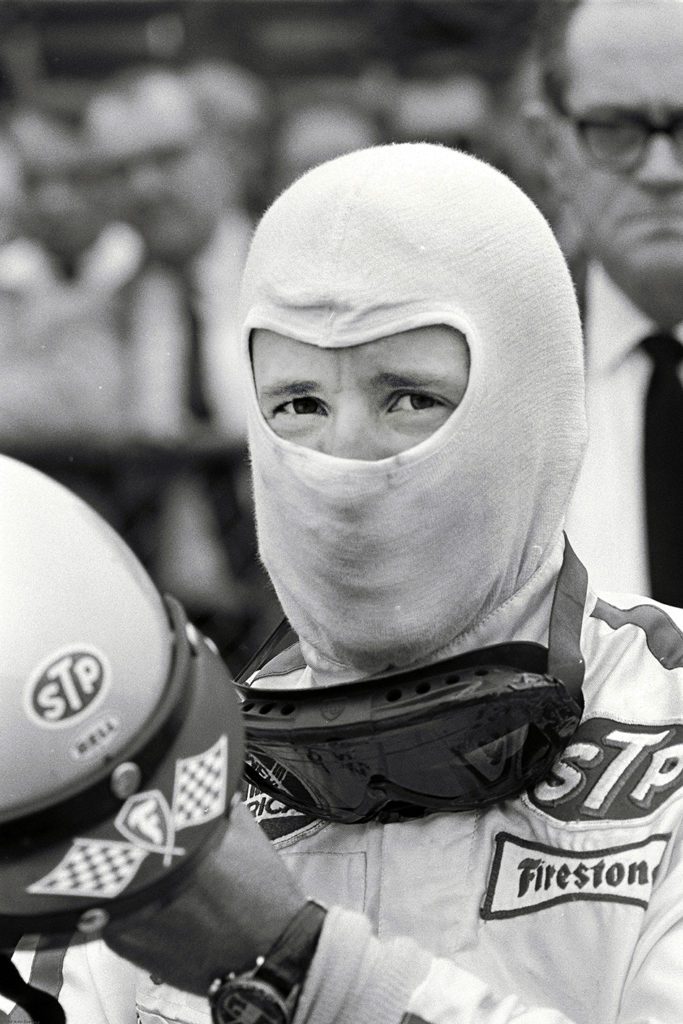

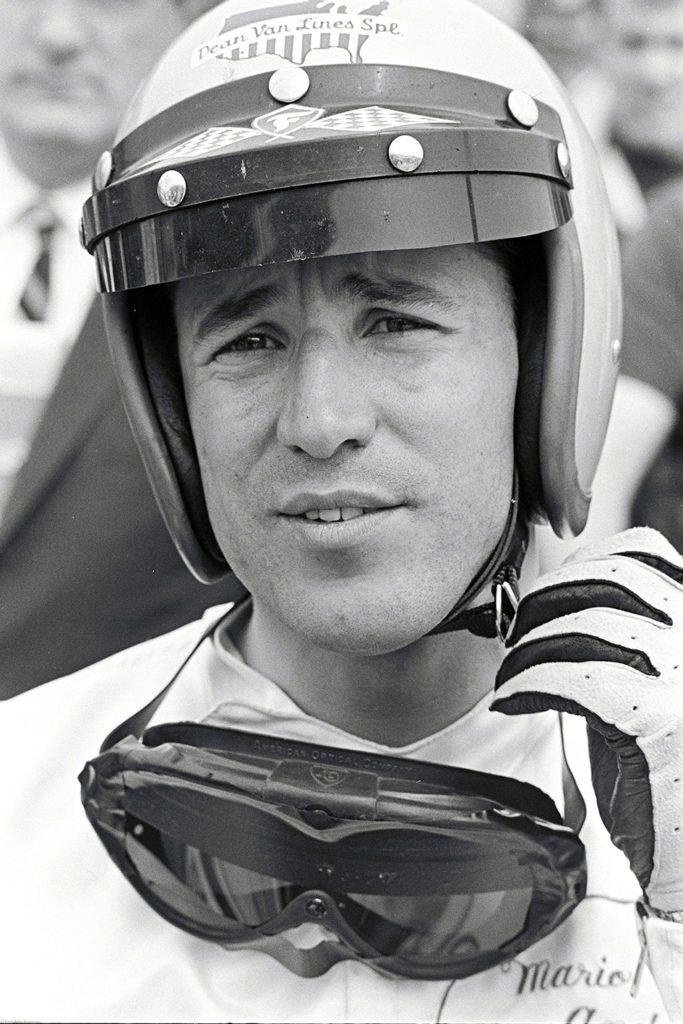

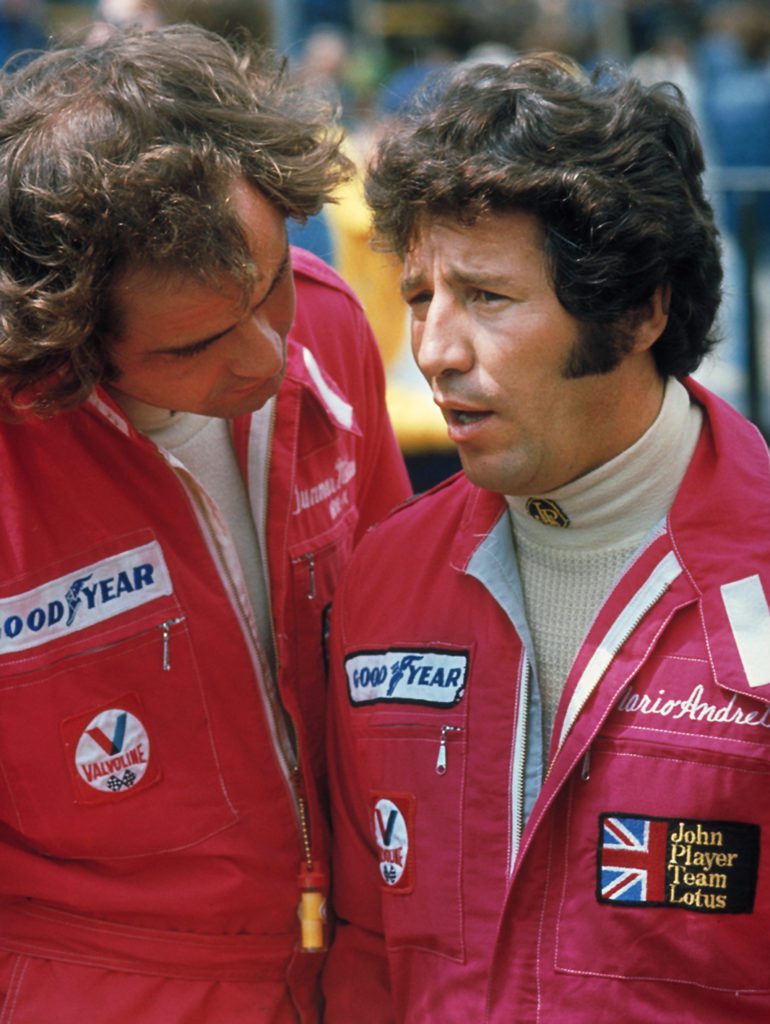

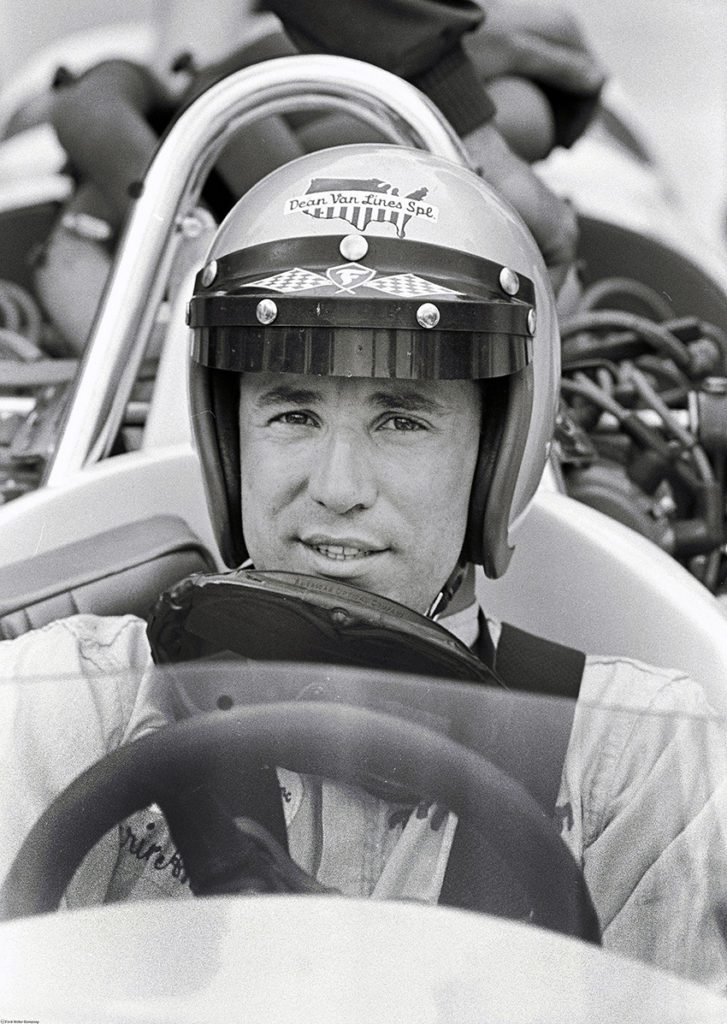

Mario Andretti is one of the world’s true sporting legends. Born in Montona, Istria, part of the Kingdom of Italy (now Motovun, Croatia) in 1940, his family was forced to flee their homeland seven years later after it became part of communist Yugoslavia. Following a further seven years living in a refugee camp in Lucca, Italy, the Andrettis settled in America. Once there, Mario pursued his passion for motor sport, winning a national championship in his first professional season of racing. Andretti went on to become a household name, winning in everything from dirt track speedway to Formula 1. Andretti’s biggest victories were in the 1969 Indianapolis 500 and the 1978 Formula 1 World Championship. In part one of an exclusive two-part interview, Andretti tells Darren House, about life as a refugee, his incredible rise to fame and the real story behind the Lotus ‘wing’ car.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 2016

AUTO PARTS AND EQUIPMENT: WHAT WAS LIFE LIKE FOR YOU IN THE REFUGEE CAMP?

MARIO ANDRETTI: We pretty much left our home when I was eight years of age and I spent seven and a half years in a refugee camp in Tuscany, in Luca. At the age of 15 we came to America. It was tough but I didn’t know a different life. When I was born in 1940 WWII broke out in Europe.

Even as a child you detect that things are not right, where your whole family argues and you see tears but that’s all I knew. The first five years of my life was war and after that it was even a bit worse because we became displaced. That was by choice because the area where I was born, became occupied by Yugoslavia, which was hard-line communism under Marshal Tito. My dad had a choice to succumb to communism and have that type of life or just leave. Like us, thousands and thousands of others in that region just left.

IT WAS A HUGE DECISION TO MOVE TO A FOREIGN LAND, SPEAKING NO ENGLISH.

It was. It was a new life for all of us, especially when we came to the ‘States. I remember when my dad was still here we had many conversations about it and he always said it seemed to be such a big negative in our lives and it all turned out to be an enormous positive. Looking back at many aspects of my life, I always felt that after the clouds comes sunshine. There is always a way that things are going to turn into a positive and it certainly did for me, on many fronts. So I look back and say, okay, it was not a normal life as we know normal lives but all-in-all, it worked out for the best so I have no anguish about that.

HOW DID YOU FIT INTO AMERICAN LIFE?

We came to a small town where I live still (Nazareth, Pennsylvania), and there was a little bit of separation with the ethnic groups. The Italians were not the most popular people here but we were naive about it. A few years later we were in a position to build a new home and my dad bought some property from probably the wealthiest family in Nazareth who were Pennsylvania-Dutch, as they call it. They almost said, ‘how dare you, as an Italian, want to buy a property next to ours’. Then we became best of friends as time went on. But again, if there were obstacles, they didn’t affect us. We just went on with our business and the town went on to receive us in great fashion, naming streets differently and all that.

HOW DID YOU BECOME INTERESTED IN MOTOR RACING?

Early in life, the most remote aspect of our lives was motor racing and yet there was something that sparked in me – I wanted to be daring about something. We had this little buggy and there was a narrow, narrow street because we lived in a medieval town – it was founded in the fourth century – and it curved in front of our house, and here we were coming down in a buggy and trying to run over old ladies and things. There was something dare devilish about my twin brother Aldo and I. Later, when we were in the camp, we were exposed to some local motor racing and it just captured my imagination at a young age.

Aldo had the same dream. We didn’t even have an automobile – my dad did not own a car until we came to America.

HOW DID THAT PASSION DEVELOP INTO A CAREER?

I don’t know why I became so passionate about it. Maybe it’s because when I was so young and impressionable it seemed so far away – like the impossible dream. I said to myself, God, if I could just pursue that, it would be all I would ask of my life and that is really what it came down to. I had no Plan B for my life and I had no idea how or when this thing was going to develop. It just did. The last race we had seen in Italy was the Italian Grand Prix, where Fangio won, Moss was second and my idol, Ascari, third.

Well, that seemed really far away but when we arrived in America in 1955, Aldo and I discovered there was a local racetrack. It was a typical half-mile dirt track with weekend racers but we looked at that as, ‘Oh my God, this could be the beginning’, and it was. Two years later we started building a car and the objective was to race that car by the time we were 21 because to race professionally in those days, you had to be 21. The car was finished in two years when we were 19 and we figured we were not going to wait, so we had our licences fudged by a friend of ours in town who was the editor of a small newspaper and we started racing.

HOW DID YOU PAY FOR YOUR FIRST RACE CAR?

We were going to school, so we weren’t working but at night we worked for a man who was married to one of our cousins. He had a gas station. Aldo and I would each work every other night and we were making $45 a week (laughs). The investment we made on the car was $1,000. We put together about half of that with four buddies, and we had a good Samaritan sign a bank guarantee, which enabled us to take the other $500 as a loan.

WHAT DID YOUR PARENTS THINK OF YOU GOING INTO MOTOR RACING?

My dad was vehemently against it, mainly because he didn’t follow it. The only thing that he knew of it was fatalities because that was what was always publicised, so we didn’t dare tell him that we were going to race. We went through the whole first season without him knowing. At the end of the season, we had been successful enough to be invited to race at Hatfield. I got a ride with somebody else and Aldo was driving our car and during a qualifying race he had a huge accident – he was trying to pass the track champion for the lead and he got into the guard rail and went end over end. That night he was in the hospital. He had a fractured skull and they gave him the Last Rites. That was traumatic and I had to be the one to tell my parents.

My dad felt vindicated, saying, “I told you so” but I had already started building a new car with my buddies for the following season. Aldo was in a coma for weeks and I would tell him about the new car because the doctors said talk to him about things that will stimulate him and eventually he came around. My dad thought that we had learnt our lesson but the following season, when our dad found out we were racing again, he had a small explosion and he didn’t speak to us for several months. He realised later on that we were going to pursue it anyway and he became a staunch supporter.

I would look back at the end of every season and ask myself, ‘Am I better off than I was a year ago? Did I progress?’, and the answer was always yes.

ALDO’S INJURIES DIDN’T GIVE YOU SECOND THOUGHTS ABOUT RACING?

No, it was a psychological set back but if you are committed to it, you’re just going to do it. Throughout my career I lost my closest friends but you go on because you love it and you have the feeling that you have some control and that it is never going to happen to you. Aldo had to take a year-long sabbatical and by the time he came back to racing I had moved onto single seaters and so he drove our stock car. He drove for 10 more years until 1969 and then he had another huge accident in a sprint car, which I owned. He never drove after that.

AT WHAT POINT DID YOU THINK YOU COULD MAKE A CAREER OUT OF RACING?

It was not an overnight revelation; you go from stepping stone to stepping stone. I would look back at the end of every season and ask myself, “Am I better off than I was a year ago? Did I progress?”, and the answer was always yes. That was all I needed to know. I was making progress and gaining experience and I was always shooting for the stars – I wanted to be at the very top. I had victories in some of the minor categories, winning against some of the top drivers at the time like AJ Foyt, so I thought when I progress to CHAMP Cars (Indy Cars) I should be okay.

DID YOU HAVE SOMEONE TO GUIDE YOU?

I wish I could have but there was no one to guide you. You were learning through the school of hard knocks (laughs). You had to just experience it and learn from others. No one of any stature was willing to take you under their wing. They always sneered down at this ‘young kid’, so you had to prove yourself. You had to do it on your own and those were the toughest times. One of the drawbacks for me was the fact that I am fairly small in stature physically and in those days you needed to look like Hercules to drive those cars. Some of the owners would look at me and ask me if I was strong enough and I would reply, “As long as I don’t have to lift the car over my shoulders I will drive it. I guarantee you I am in condition to do it physically”. It was another thing I had to prove that I could do, and I did.

HOW DID YOU ADAPT FROM A DRIVING STYLE THAT REQUIRED BRUTE FORCE TO ONE THAT REQUIRES FINESSE?

Of all of the experience that you gain from the different disciplines, something is always applicable no matter what you are driving. It’s about car control, it’s about being able to feel how to get the power to the ground without wasting a lot of time wheel spinning. For example, I applied some of the car control and the driving skills that I developed driving on the slippery surface of dirt track ovals; some of that helped me in the wet during a road race because on some of the dirt tracks, the conditions changed so dramatically. You had to adapt to it and that is what it is in wet conditions on a road course – almost every lap is different. So, everything was applicable somewhere.

YOU PROVED THE VALUE OF THAT EXPERIENCE IN THE VERY WET 1976 JAPANESE GP

Yeah, it wasn’t easy. The strange thing was that the Europeans always thought Americans could not drive in the wet because they are not trained to and that was one point where I wanted to prove them wrong. I like to think that I can drive as quickly as anyone in the wet. I think I have proved that several times throughout my career and that’s what you are looking for as far as personal satisfaction.

When you can’t put the results together, the driver blames the car and owners blame the driver (laughs).

YOU MET COLIN CHAPMAN IN 1965 – WHAT WAS HE LIKE?

Colin was a real genius as we all know and a very interesting guy. If you were on the right side of him you were golden. Fortunately, I think that’s how things were for me because in my very first race with him I put the car on pole and I was the third man on the team, so it was an auspicious beginning. Later on, when we joined forces again we won a World Championship so we were scoring. As long as his drivers were getting results, he loved them so we developed a great relationship but I saw a different side of him towards some of the other drivers.

YOU DECLINED HIS EARLY OFFER TO DRIVE FOR LOTUS. WHY DID YOU TAKE SO LONG TO ENTER F1 FULL TIME?

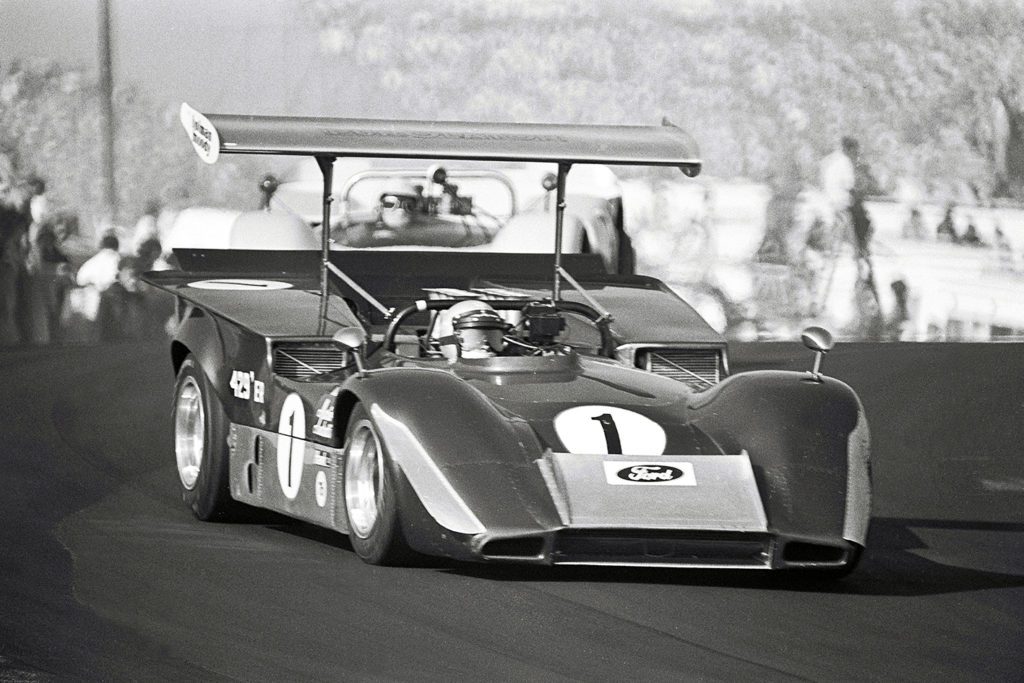

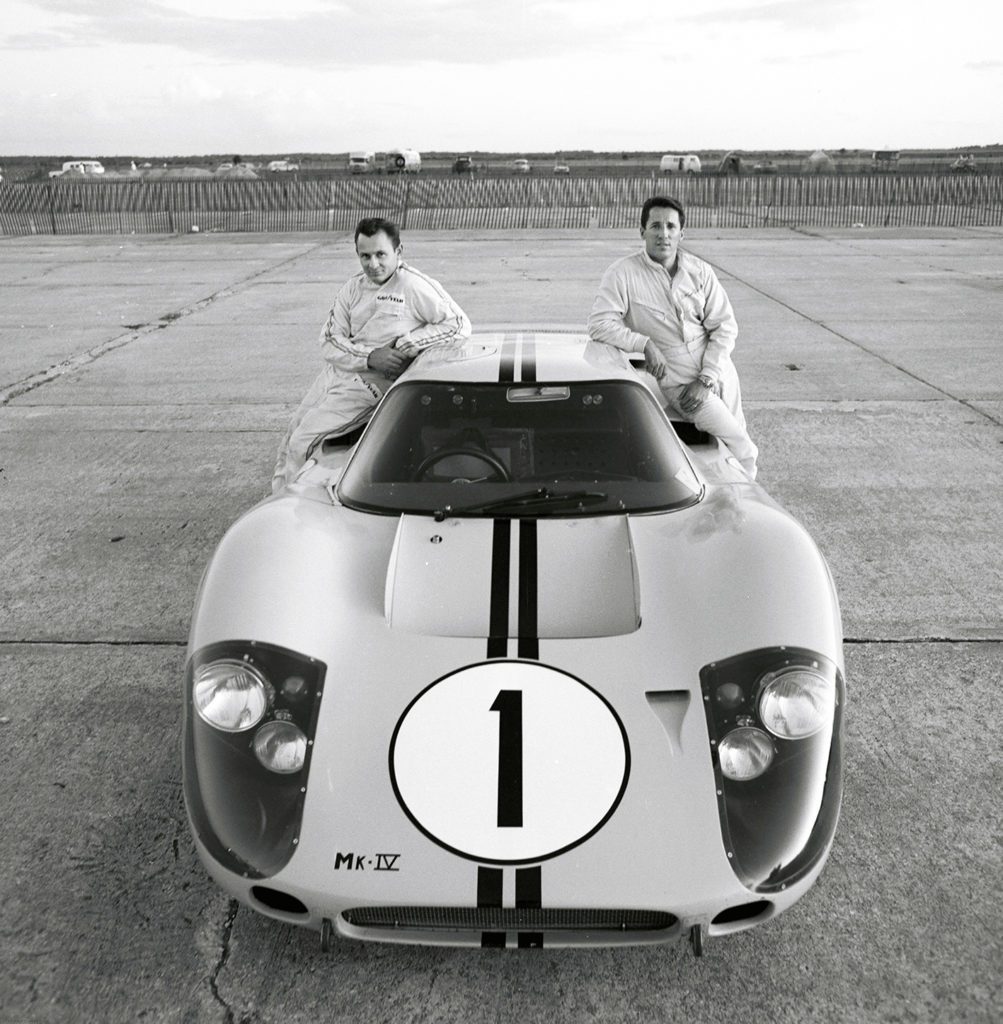

First of all I had to try to hone my skills in road racing before I could attempt that – I felt that I needed time before I could venture into F1 but at the time I was involved in Ford Le Mans programmes and that allowed to me to do a lot of testing. One driver who was very helpful to me was Bruce McLaren. He and I became really good friends and I learned a lot from him without him even knowing; just by watching him, and then asking questions. This was later in my career where I felt I was at the same level and could discuss things and get the answers.

Also, the problem was I couldn’t really commit to full time (F1) because I had quite a relationship with Firestone. From a financial standpoint, things were becoming quite attractive and I couldn’t leave that, not that I ever raced for the money but it represented stability for me and my family. I figured if anything happens to me at least my family will be taken care of by earning what I was earning.

[Chapman] said, “Why don’t you come with me (though) our car is really not good right now, it’s like a London bus”.

BEFORE JOINING LOTUS FULL TIME YOU HAD AN UNPLEASNT EXPERIENCE WITH THE PARNELLI JONES TEAM.

It’s very frustrating when things don’t go well and there is finger pointing and all that. It is the worst possible scenario and unfortunately that is what happens when you can’t put the results together – the driver blames the car and owners blame the driver (laughs). But again, you always learn something, even from that. The switch from Parnelli to Lotus was something that was not designed – it just happened – and is another perfect example of a negative becoming a positive. At the beginning of the ’76 season we were at Long Beach (California) on the grid when I learned that Parnelli Jones had decided to quit F1. We had a DNF in the race and Colin Chapman had probably the worst race he had in his career, one of his cars didn’t even qualify. Colin and I were having breakfast the next morning and I said, “Colin, the team quit F1 and I’d really like to continue”. I thought that he was committed with his drivers but he said, “Why don’t you come with me (though) our car is really not good right now, it’s like a London bus”.

I said, “Colin, if you come back to racing 100 per cent – because at that point he started a boat company, he started a car company and he was very much distracted – if you delegate authority to others for those businesses, I’ll do it”.

DID YOU KNOW THE GROUND EFFECTS CAR WAS ON THE WAY?

A lot of people don’t know the history of it. Ground effects happened by accident – we had no idea. Actually, I am the one who suggested the side pods because of the experience that I had with the 1970 March, which had side pods that created a downforce effect. A lot of people didn’t realise it but I did when I was testing at Kyalami in South Africa. I thought maybe those things create unnecessary drag so we took them off and all of a sudden the car was really flying in the front end – we lost a lot of front downforce. We thought gosh, we are going to have to put them back on to regain the balance.

Throughout the 1976 season we had some issues but we kept talking and I tried to make some suggestions but Colin didn’t like that. He didn’t like to hear technical things from a driver but at the end of the season we sat down and a question was thrown at me, “Okay Mario, what would you like to see in the new car?” I said downforce with no drag penalty and then I would chuckle because that’s impossible, right? I got their minds ticking over and then I explained to them the effect of the March pods.

Colin then went further, he put side pods on the car but he also put the straight fences on them to be able to direct and contain the air and that is how the ground effect began. Nothing was studied in a wind tunnel; that came later when we had to come up with skirts and all that sort of thing. It was just one thing leading to another. There was no, ‘Oh, we just discovered ground effects on paper’.

HOW DID THE SPORT CHANGE DURING YOUR LONG CAREER?

I went through different decades where the sport evolved in every way – technology, engines, plus all of the learning curve of aerodynamics. I feel very fortunate, because I think it was fascinating to say the least. One thing that kept me motivated was that every year there were break throughs – something to look forward to. Now things are not that interesting because the knowledge is so vast, all you are doing is changing rules to eliminate this and that. The technology that I experienced, especially with the Indy Cars back in the ’90s has, if anything, gone backwards because of the rules. Our cars were more sophisticated in the ’90s than they are now.

In part two we look at the later stages of Mario’s career, including his 222mph (357km/h) crash at the age of 63.